|

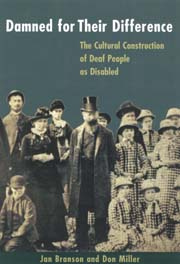

The Cultural Construction of Deaf People as Disabled

Jan Branson Read chapter two. $76.00s casebound |

Shopping Cart Operations

Add to Cart |

From the Journal of Social History

In Damned for Their Difference, Jan Branson and Don Miller have written an important and provocative book that contributes to the growing debate in disability history about the nature of difference and how it is culturally defined.1 Their subject is the “cultural construction of deaf people as disabled” in Britain from the seventeenth-century to the present and to a lesser extent in Australia for the modern period. Branson and Miller, who are both sociologists, contend that earlier writers have seriously misrepresented the history of deaf people in Britain; therefore they view themselves as revisionist researchers. (p. xii) In their study, the authors present a wide-range of historical and cultural evidence from the age of Scientific Revolution to the age of the cochlear implant in an effort to explain why deaf people have been marginalized and treated as disabled.

In chapters one and two, Branson and Miller delve into some of the conceptual issues that provide a cultural framework for their study. These chapters provide an extensive discussion of why hearing people often labeled deaf people “abnormal” or “pathological.” They broadly paint the impact of early science, the culture of evolution and imperialism and then eugenics, relying on the theories of Weber, Foucault and Bourdieu as underpinnings to their study. In each of these historical periods, the deaf were doomed to exclusion because they did not neatly fit into any set definition of “normal.” For many historians, these observations will seem too broad and overtly sociological, but the authors do capture the “disabling process” in uncanny ways. For instance, the introduction of the intelligence (IQ) tests for young children at the turn of the twentieth-century marginalized disabled children in public schools in new ways. (p. 47) Now educators and psychologists claimed they could measure brainpower; science could prove that the deaf were deficient. The authors conclude this conceptual part of their book with a criticism of mainstreaming disabled students into “regular” schools in the last decades of the twentieth century. Rather than encouraging integration between “normal” and “disabled” students, they contend that mainstreaming practices have actually resulted in more isolation and discrimination. (p. 54) This important and contentious point is further discussed in chapter eight.

In part two of their study (chapters three through nine), Branson and Miller employ a more historical approach to the material. One of their key points is that deaf people from the seventeenth century onward were increasingly pawns in a larger “intellectual game” that involved the dissection of language and its use to measure rationality among the masses. (pp. 86—87) The authors refer to Abbé de l’Epée, the Jansenist priest who taught deaf children in Paris in the years before the French Revolution, as one who was fascinated with rational grammar in his search for a universal language.2 Branson and Miller pinpoint the great divide between Britain and France in the education of deaf children from the era of Epée and Thomas Braidwood. There were two main differences between the French and British methodologies in the late eighteenth-century: rational language versus natural language and the “clinical gaze” in France versus the missionary/charitable focus of British deaf schooling. (pp.112—113) Once Branson and Miller make this assertion, their book turns to developments in Britain with only occasional comparisons to France. However, the claim that the British in the first half of the nineteenth-century saw deaf children as “objects of pity, in need of charity” (p. 125) scarcely differs from the situation in France where secular teachers and religious orders were routinely involved in a variety of instructional experiments with deaf children. This is one area where the authors’ absolute dichotomy between Britain and France breaks down.

In chapter 6, Branson and Miller discuss the interconnection between disabling deaf people and the eugenics movement of the late nineteenth-century. The chapter, in fact, encompasses many different issues: evolutionary theory, eugenics, oralism and the Milan Congress of 1880. The authors argue that British schools for the deaf were not oralist (predisposed to spoken language) through out most of the nineteenth century. (p. 156) This is where Branson and Miller’s revisionism is most evident. Most researchers have identified British reliance on fingerspelling (rather than a form of signed language as developed in France by Roch-Ambroise-Auguste Bébian) as at least a precursor to oralism.3

In the last chapters of their study, Branson and Miller discuss the alienation of the deaf child in a modern bureaucratic system where teachers, doctors and social welfare personnel regarded the deaf as in need of “therapeutic treatment” to offset their deafness. (p. 187) The authors accurately point out that residential schools for the deaf, which encouraged deaf community identity, came under attack from various deaf educators (including Alexander Graham Bell) because they inhibited full integration with the hearing community. (p. 192) In this sense, Britain, France and America shared a similar educational experience that disabled their deaf. Branson and Miller critically address the impact of this “normalizing” treatment on deaf people for the early twentieth-century when audiologists played key roles in determining who was “treatable” for residual hearing. Today surgeons and audiologists routinely fit deaf children with cochlear implants in an effort to return them fully to the hearing world.4 The authors have explicitly identified this cochlear technology as “the new oralism” that is supposed to cure deafness once and for all. (p. 228)

In Damned for Their Difference, Branson and Miller have presented a wide sweep of Western history (mostly British), linking the advent of the modern bureaucratic state with the disabling of the deaf minority population. As sociologists, they try to draw larger conclusions about “linguistic imperialism” (p. 248) in a modern world that readily adopted cultural and economic imperialism. Historians will not be satisfied with the textual analysis of the sources or with the progression of argument, but the authors do provoke critical review of the disabling process in Western society. By engaging us in the debate, Branson and Miller make us think more deeply about what is “normal” in our own society.

Jan Branson is a former director of the National Institute for Deaf Studies and Sign Language Research at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Don Miller is a former head of the Department of Anthropology and Sociology at Monash University in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

ISBN 978-1-56368-118-9, 6 x 9 casebound, 320 pages, illustrations, photographs, references, index

$76.00s

ISBN 978-1-56368-121-9, paperback

$43.95s

![]()

To order by mail, print our Order Form or call:

TEL 1-800-621-2736; (773) 568-1550 8 am - 5 pm CST

TTY 1-888-630-9347

FAX 1-800-621-8476; (773) 660-2235