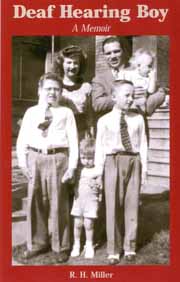

A Memoir

R. H. Miller

September 2004

|

View the table of contents. Read chapter seven. Read reviews: The Courier-Journal, Library Journal, The Midwest Book Review, Disability Studies Quarterly. |

$22.95t print edition $22.95 e-book |

Deaf Lives, Volume 2

Louisville author Robert Miller grew up in unusual circumstances — he was the hearing son of deaf parents.

Born in Defiance, Ohio — named for General “Mad Anthony” Wayne’s fort at the confluence of the Auglaize and Maumee rivers — he grew up dealing with the superstitions, prejudices and the more benign realities of having “handicapped” parents.

In the course of this history, Miller tells a touching story about his own coming-of-age, and corrects many of our misconceptions about the hearing-impaired — for one, deaf parents rarely have deaf children (this one, his grandparents worried over ceaselessly).

This memoir also nudges us out of our hearing-ethnocentrism. Robert Hoffmeister’s forward tells us, “The Hearing world believes that deaf people should want what the Hearing world wants for them.” But of course this is not true.

The deaf world has its own culture, and its own desires, and is quite capable, beyond our prejudices, of operating — quite deftly — on its own.

Miller’s father was not born deaf, but acquired deafness as a result of childhood meningitis. He is, according to the nomenclature, an “accidental” deaf person. Though his mother was born deaf, Miller’s own children had no greater chance of being born deaf than the average population. This did not stop him from rattling his keys over their crib when they were infants, just to check.

Miller’s parents struggled with deaf-education in their day. Believe it or not, there was a time when sign language was forbidden in deaf schools. Speech-reading — what we know as lip-reading — or oralism, some thought to be a better way to mainstream deaf students. But it did not work. Miller’s parents did quite well, as people in the world, and as parents, using sign language to keep up with world events and with their active children, especially the oldest, who liked to sit on the very edge of counters and play with dangerous kitchen implements.

Miller recalls, with sadness, how his mother constantly denigrated her own intelligence, a prejudice instilled in her after decades of cultural ignorance. It pained him to see her using the ASL [American Sign Language] sign for stupidity, “the clenched fist rapped against the forehead. No matter how much I tried to convince her that her problems were caused by early learning deprivation,” he writes, “she always felt inadequate.”

Miller’s parents encountered additional hardships when forced to move from the family farm near Defiance to the relatively big city of Toledo in 1942. There was a larger support system for deaf people in the city, and they got rather used to it, but then had to move back to the farm, in 1949, and forsake those advantages — following, then contradicting, much of the mid-century flight of the greater American population. This exacted a higher toll on his parents than it might have done on hearing parents, if only because resources became so scarce.

Miller writes evocatively of being perceived as the “other” by teachers and administrators, but feeling quite “normal” as a kid. “As a child of deaf parents, I always felt that I would forever be an ‘other,’ a member of a marked minority, and that it was incredibly naïve of me or my teachers to think that I would ever ‘fit in.’ I was not the problem; my teachers were the problem. If not my identity as a CODA [Child of Deaf Adults], then my intense shyness would always mark me in some way as being a kid apart, and I had a right to be treated honestly by a world that had set my parents apart. The hypocrisy of their attitude was too obvious to me.”

His mother’s difficult life notwithstanding — she worked 25 years pressing shirts for a laundry — she has had “the good life,” Miller writes, and survives to this day, with her husband. They recently celebrated their 65th wedding anniversary.

Miller’s writing is crisp and evocative. When, in 1998, his brother suffered a burst aneurysm, and because of a ventilator could not talk, “as if it were second nature to him,” Miller writes, his brother communicated with him through sign language, closing their visit with the sign for love, the fist tapped on the heart then fingers pointed to the loved one.

Miller has written a moving and loving memoir. The book is a testament to the parents who, while deaf, instilled in him a love of language and an empathetic heart.

R. H. Miller is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Louisville.

Print Edition: ISBN 978-1-56368-305-3, 5½ x 8½ paperback, 176 pages

$22.95t

E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56368-280-3

$22.95

To order by mail, print our Order Form or call:TEL 1-800-621-2736; (773) 568-1550 8 am - 5 pm CST

TTY 1-888-630-9347

FAX 1-800-621-8476; (773) 660-2235