|

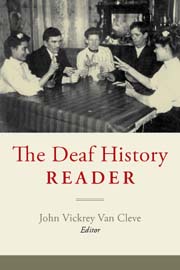

John Vickrey Van Cleve, Editor View the table of contents. $24.95s print edition |

Shopping Cart Operations

Add to Cart |

From The Sign Language Translator and Interpreter

The Deaf History Reader is a collection of related essays on historical research that brings to light past Deaf experiences in the USA. It covers a variety of issues of relevance to those interested in Deaf history and Deaf studies, but has some linking themes to other disciplines, such as education, politics or sociology. The nine chapters are not arranged in any specific order, and therefore this review will not deal with the chapters chronologically but rather discuss each located around the subject matter they hold in common.

The history in question concerns the period of the USA from the 17th to early 20th century but the main era covered focuses on the 19th century. While the majority of the chapters cover specific aspects of local Deaf history, attempts are frequently made at offering a broader analysis of Deaf communities through this historical period, discussing many issues which remain relevant for today and the future.

The late 19th century was the time during which the infamous Second International Congress on the Education of the Deaf took place, in Milan in 1880. Its relevance for this period and beyond shines through in the numerous references to this event throughout the book. The congress declared the superiority of oral methods of instruction (by the use of speech) over those of sign language, declaring that all deaf children should be taught using the oral method (also referred to as oralism). After this period, schools worldwide began to favour oralism. The chapters by Crouch and Greenwald on Hearing with the Eye, by Van Cleve on The Academic Integration of Deaf Children and by Reis on A Tale of Two Schools, focusing on educational issues, particularly outline the impacts that the event had on Deaf people’s lives. However, the book encourages us to go beyond viewing the Deaf world in this period in terms of the vexed subjects of education and Milan only, by illustrating what was actually happening around Deaf people’s lives during this era. Further issues explored in the book range from a discussion of the impact of Alexander Graham Bell’s involvement in the eugenics movement (Greenwald) to accounts of how local communities succeeded in setting up religious services (Olney) and services for vulnerable Deaf people (Boyd and Van Cleve). Put together, the contributions thus have the combined impact of giving the reader a sense of what issues the community and individuals were engaged with during a time of significant and long-lasting change that resulted from Milan 1880.

The editor of the book, Van Cleve, claims in the Preface that the research undertaken and evidenced in the articles challenges some of our existing assumptions about the Deaf community in the USA during this period (p. vii), which is certainly borne out in several respects. In Genesis of a Community, Lang’s historical research on the development of American Sign Language (ASL), for example, locates Native Americans and also colonialists from Great Britain using sign language well before Laurent Clerc and Thomas Gallaudet arrived from France in the early 19th century. As he suggests:

... the gestures and signs used by deaf people in the various American colonies and the French signs brought to America by ... Gallaudet and ... Clerc likely merged with the various existing sign language varieties, especially those brought to the school by the first students. (p. 9)

ASL is therefore likely to have arisen from a ‘melting pot’ of localized sign languages rather than simply having been transported from overseas, which is evidenced in detail by the authors.

One chapter which particularly challenges historical assumptions is Greenwald’s essay Taking Stock on Alexander Graham Bell. Greenwald argues that, although being well known for disapproving of Deaf marriages, Bell did not support any official radical eugenicist programmes, such as prohibitions on marriages or sterilization. Greenwald therefore ‘humanizes’ Bell while never losing sight of his actions in advocating oralism and eugenics.

Many of the articles locate the importance of Deaf people in the process of making history, particularly in the setting up of Deaf schools and organizations (see, for example, the chapters Hearing with the Eye by Crouch and Greenwald, A Tale of Two Schools by Reis, Deaf Autonomy and Deaf Dependence by Boyd and Van Cleve, and The Chicago Mission for the Deaf by Olney). Taking the book as a whole, we are encouraged to view the development of the Deaf community in this period as a complex process, involving much wider forces than the efforts of single persons. At times, however, particular individuals stood out who caused significant changes. In his chapter on A Tale of Two Schools, for example, Reis contrasts two Indiana day schools; while highlighting the behind-the-scenes politics and sources of wealth that shaped the development and the progression of these schools, Reis places particular emphasis on the achievements of Charles Kerney in the process, a Deaf man who established one of the schools. The chapter, however, does not hide the hypocrisy of Kerney’s wealth on the one hand, and the poorly funded school and the impact the lack of funds had, on the other hand.

John Vickrey Van Cleve is Professor Emeritus of History at Gallaudet University.

Print Edition: ISBN 978-1-56368-359-6, 6 x 9 paperback, 226 pages, 3 tables, 4 figures, 11 photographs

$24.95s

E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56368-403-6

$24.95

To order by mail, print our Order Form or call:TEL 1-800-621-2736; (773) 568-1550 8 am - 5 pm CST

TTY 1-888-630-9347

FAX 1-800-621-8476; (773) 660-2235