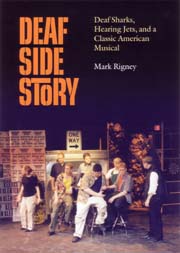

Deaf Sharks, Hearing Jets, and a Classic American Musical

Mark Rigney

|

View the table of contents. Read the prologue. Read reviews: Santa Barbara News Press, The Boston Globe, SIGNews. |

$24.95t |

From The Boston Globe

It was nothing less than “a spark, a flash” in the theatergoers’ lexicon. The combustion emanated from the Broadway classic “West Side Story,” as played out in Illinois by a part-deaf, part-hearing young company.

It was a joint venture between MacMurray College and the Illinois School for the Deaf in 2000. And it nearly didn’t happen.

The play’s plot, as author Mark Rigney reminds us, “is a barely altered adaptation of William Shakespeare’s ‘Romeo and Juliet,’ with street gangs standing in for the Bard’s Capulets and Montagues.” The show first opened on Broadway in 1957. Thanks to Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim, and Arthur Laurents, it’s brilliant but difficult music and dance, even without the deafness factor. But author Rigney’s wife, Diane Brewer, who in 1999 was the newly named drama head at MacMurray, decided to take on the deaf/hearing mix. And once her decision was made, the aforementioned sparks and flashes flew indeed.

For starters, those responsible for the Illinois project were worried that the deaf/hearing divide could be a self-fulfilling prophecy, leading to the sort of divide that “West Side Story” condemns. Rigney writes: They “are concerned that the students will be enticed into acting out the violence in the script, internalizing it, romanticizing it,” and perhaps being drawn to such behavior. (That proves a baseless fear.) There are practical matters of stage placement, not to mention costumes for characters who are signing alongside various main actors.

Early on, the cast can be found huddling in a basement, waiting out a tornado alert. (Again, ultimately, there’s no cause for alarm.) There are the flares of temperament that often coincide with creativity. And, not least, it turns out that Brewer is pregnant.

Rigney’s account of this small tale of an unusual production is intelligent and humane. For example, he demonstrates both sensitivity and humor in the encounters that occur among the deaf. Discussing the interplay among the cast and crew, he records: “Embarrassed by her poor signing, Terri tells Christopher through [a third character], ‘If I sign something dumb, like “Your mother is a cow,” you can assume that isn’t what I meant.’

“Christopher nods and smiles, ‘O-Kay,’ choosing one of his favorite words. Under his guidance, the two syllables twist and stretch into something far greater than the word was ever meant to be; when Christopher says ‘O-Kay,’ it becomes a sort of a blessing.”

And there are other realms of communication that the hearing reader may take for granted.

Rigney suggests at one point that Laurents’s ’50s-style slang, much of which he invented, causes everyone fits. In some cases, where idioms or jive find no American Sign Language equivalent, Carrie and the students resort to signing ‘silly, very silly.’”

Rigney gives the humor added context. “Comedy,” Laurents is quoted as saying, “is exactly what’s needed in the face of tragedy -- it’s the tension between the two that holds the audience.”

In a more serious light, there are Rigney’s artfully portrayed players. Pearlene, for instance, plays the young, deaf Maria. As Rigney relates, she “shakes her head in frustration and her hair flies across her face. ‘Why,’ she asks, ‘should I connect with the music when I can’t hear the music?’”

Then there’s the political dimension of deafness. Rigney discusses this in depth, suggesting at one point: “Lawmakers, like most Americans, don’t think about deafness any more than they think about Mars.

“In any event, the deaf community is hardly cohesive enough to form an ongoing voting block. Rough estimates suggest that some two million Americans are unable to hear spoken languages, and approximately sixteen million Americans have some degree of hearing loss.”

And, he says, in the charged sphere of deaf communications, the choice of methods “remains a controversial topic even today, and the use of speech by a deaf or hard-of-hearing person can become either unwitting or a willful political act.”

This reflection and analysis are surely germane, but Rigney is strongest when he’s closest to Brewer and the singular rendition of the show. (Ultimately, their production is a shining success.)

As Rigney says, “Maria teaches [Tony] the sign for ‘I love you,’ and they press their fingers together in a matching, mirrored tableau. . . . This is the single most important moment in the play.”

Mark Rigney is a writer whose stories have appeared in THEMA and The Bellevue Review, and whose plays have been staged at the Foothill Theatre Company, the Utah Shakespeare Festival, and the Alleyway Theatre. He lives in Evansville, IN.

ISBN 978-1-56368-145-5, 6 x 9 paperback, 232 pages

$24.95t

To order by mail, print our Order Form or call:TEL 1-800-621-2736; (773) 568-1550 8 am - 5 pm CST

TTY 1-888-630-9347

FAX 1-800-621-8476; (773) 660-2235