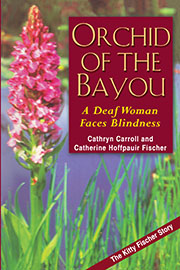

A Deaf Woman Faces Blindness

The Kitty Fischer Story

Cathryn Carroll and

Catherine Hoffpauir Fischer

February 2001

|

View the table of contents. Read an excerpt. Read reviews: Publishers Weekly, DSQ, Silent News, Louisiana History. |

$29.95t print edition $29.95 e-book |

From Disability Studies Quarterly

An autobiographical narrative of living as a congenitally deaf woman, The Kitty Fischer Story is a marvelous account of a life influenced by deafness, an Acadian-Cajun heritage, race, gender, and, ultimately, blindness caused by Usher syndrome. Fischer takes us through her life from ambiguous snapshots of her early childhood to more vivid and compelling accounts of her experiences as a nearly-blind deaf adult.

Her deafness was never misdiagnosed; rather, nearly a year after being born, Fischer’s grandmother insisted that “there’s something not right about that baby” (p. 6). Home-made experiments of banging pots and pans and a trip to the doctor’s eventually convinced Fischer’s parents that she was “deaf-and-dumb,” a misconception that nearly prevented her education. By sheer happenstance an aunt discovered the Louisiana School for the Deaf and urged that Fischer be enrolled there.

Once her education began the story takes on a much clearer voice and image of the experiences of being deaf in race-segregated Louisiana. Fischer weaves her own narrative with the history of deaf residential schools and differing philosophies of deaf education that continue to plague us today. What is most remarkable about this account is Fischer’s tenacity to continue her education through to a graduate degree despite barriers posed by gender and class. She was encouraged by teachers at the Louisiana School to take the test that would admit her to Gallaudet University, a test that she passed with flying colors. Her subsequent enrollment and attendance, however, was precariously marginalized by her feelings of filial duty and gender-influenced expectations of living and working at home. Because she was perceived as “different” she was not raised with the same demands and expectations that an Acadian-Cajun girl ordinarily would have had. For example, she was not punished for physically abusing her siblings and friends primarily because it was thought that she was not capable of “normal” social behavior.

I would argue that the greatest barrier Fischer faced was the prevailing gender expectation that women in small-town Rayne did not go to college, rather than the barriers posed by deafness. In fact, I would suggest that Fischer’s deafness aided her in overcoming gender barriers to her education by providing her with a route by which she did not have to conform to the traditional notions of the female gender.

I have to admit that as an oral, mainstreamed deaf adult, I am not wholly supportive of deaf residential schools for a number of reasons. But, after reading Fischer’s story of success, I find myself reconsidering the value of Fischer’s message: “When people ask me about educating deaf kids, I admit I am biased in favor of residential schools...but when they ask me what deaf kids really need, I don’t talk about school at all. They need each other, I say, and enough ‘each others’ to make a group of peers. They also need to know some deaf adults. Even the best hearing people can’t help deaf people become successfully Deaf; only other deaf people can do that” (p. 253).

Cathryn Carroll is the former managing editor of Publications and Information Dissemination at the Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center at Gallaudet University.

Catherine Hoffpauir Fischer is a former librarian at the Model Secondary School for the Deaf.

Print Edition: ISBN 978-1-56368-104-2, 6 x 9 paperback, 272 pages

$29.95t

E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56368-237-7

$29.95

To order by mail, print our Order Form or call:TEL 1-800-621-2736; (773) 568-1550 8 am - 5 pm CST

TTY 1-888-630-9347

FAX 1-800-621-8476; (773) 660-2235